1 The Birth of Human Rights Watch: A Product of US-USSR Confrontation

After World War II, a common problem faced by the Soviet Union and the United States was how to pick up the baton from Britain and Europe to rule the world. At that time, both the United States and the Soviet Union had strong confidence in their own systems and values. In its prime, the United States saw itself as a promised land overflowed with honey and milk, while at the other side of the Bering Strait, the Soviet Union was contemptuous of the United States and declared to the world that it would never create a Utopia for the minorities at the top of the pyramid through exploitation. Thus, the two superpowers with different ideas got involved in the confrontation, rekindling the flames of war in Southeast Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. But Europe did not want its reconstruction process to be disrupted by wars, and the United States could not just sit by and watch the Soviet Union swallow up Europe. After lengthy negotiations, the Western bloc led by the United States and the Soviet bloc signed the Helsinki Accords in 1975, which temporarily stabilized the situation in Europe at the cost of recognizing the Soviet Union’s control over Eastern Europe.

The Helsinki Accords also called for respect for human rights and protection of people’s basic freedoms, which gave the United States an opportunity to establish the Helsinki Watch. In 1978, Helsinki Watch was created to monitor the Soviet Union and Eastern European countries’ fulfillment of their human rights commitments. The organization sent a lot of monitors to the Soviet Union and Eastern European countries, and unsurprisingly many of them were arrested. Helsinki Watch quickly added a task: urging the Soviet Union to release the arrested monitors. Still, the purpose of the organization was to “promote human rights and political freedoms in the Soviet Union and regions of Eastern Europe”, and to publicly acknowledge unethical behavior carried out by governmental bodies through media coverage or on international occasions.

For President Carter, an agreement written in black and white did not mean moral equivalence between the United States and the Soviet Union. The fact that human rights were “universal” did not mean that they got equal respect everywhere, or that some people were not more qualified than others to promote them. Human rights were universal theoretically, but American essentially. The United States had an obligation to promote human rights in the world. In his inaugural address, Carter said: “there can be no nobler nor more ambitious task for America to undertake on this day of a new beginning than to help shape a just and peaceful world that is truly humane”. Carter described the task of the United States from the perspective of universal human rights, so the differences in the Cold War could be bridged by the illusion of similarities. The United States and the Soviet Union at least shared some basic principles on paper. Fortunately, the special political traditions of the United States make it a better place for those principles to take root.

With the expansion of the Soviet bloc around the world and the need for Helsinki Watch to adapt to the changes in the policies of the U.S. government, Asia Watch (1985), Africa Watch (1986), and Middle East Watch (1989) were established successively. In 1988, all of these organizations were united under one umbrella to form Human Rights Watch.

It was 44 years since Roosevelt’s Gambia speech, and three years before the collapse of the Soviet Union. On the eve of the collapse of the indestructible union, the United States finally did not need to worry that the Soviet Union would compete with it to seize control of colonies. As the world situation changed, the main responsibility of Human Rights Watch shifted from criticizing the Communist system and leaders to influencing government decisions through important politicians. However, this was not the first time that the organization had been forced to shift its focus to maintain its legitimacy.

2 Cooperation and Entanglement: the Formation of a Symbiotic Relationship between Human Rights Watch and the US Government

At the beginning of its establishment, Helsinki Watch faced many financial, administrative, and organizational problems. The root of its internal problems was that Helsinki Watch had not yet identified its own position. For one thing, the organization, with a condescending paternalistic attitude, “spoke” for the victims of Communist oppression in the name of human rights that Americans “took for granted”. For another thing, it represented a response to the model established by the founder of Moscow Helsinki Group and that model had not transformed into the source of legitimacy in the American context. Although Helsinki Watch’s initial strategy—attacking the Soviet bloc by criticizing the Communist system and covering Communist leaders negatively—proved to be ineffective, such an attempt still had its value.

Therefore, it can be said that Helsinki Watch’s attempt to deal with tensions played a great role in determining America’s future policy direction when the Cold War grew in intensity. For Helsinki Watch itself, its further expansion would depend on how the organization redefined its role in the face of a changing geopolitical environment.

During the presidency of Jimmy Carter, Helsinki Watch established a comprehensive alliance with the U.S. government. Carter declared in his inaugural address that “our commitment to human rights must be absolute”, which meant Carter connected the interests of the United States with values universally accepted in theory. This connection implied that the United States did not support a particular ideology or system of government, but global interests: “we will fight our wars against poverty, ignorance, and injustice—for those are the enemies against which our forces can be honorably marshaled”.

At this time, the Cold War was becoming increasingly intense, but America’s geopolitical rival, the Soviet Union, was absent in this speech. The act of playing down its rival ensured that “justice” represented by the United States was absolute, and it also aimed to prove that Helsinki Watch played an important role that went far beyond ideological confrontation and was significant for the sound development of the human world.

Ronald Reagan’s election as president brought an abrupt end to the alliance between Helsinki Watch and the U.S. government. After taking office in January 1981, Reagan immediately redefined the provisions of the Cold War. In the Reagan era, democracy replaced human rights becoming a new source of American justice. The United States under Reagan would represent a specific political system rather than a universal code of ethics derived from presumptive global consensus. Reagan’s attitude towards the Cold War greatly shook the legitimacy of Helsinki Watch, and its close relationship with the U.S. government formed during Carter’s term was also in jeopardy. If the organization used to regard itself as an alliance to protect the dissidents in Eastern Europe, with Reagan coming to power, its main threat changed from the Soviet Union to Reagan’s new definition of the Cold War.

In order to defend its legitimacy, Helsinki Watch decided to attack the strategic alliance between the Reagan administration and right-wing governments in Latin America on the ground that the Reagan Administration’s economic and military aid destroyed the local human rights environment. The organization tried to show its neutrality by submitting such false statements to the media. To this end, America’s Watch was established with the goal of promoting human rights throughout America and protesting Washington’s foreign policy. It also emphasized that the organization was neither right nor left, but only concerned with protecting human rights violations wherever they occurred.

Americas Watch spent most of its time lobbying the U.S. government rather than improving the human rights situation in South America and eventually opened a permanent office in Washington, D.C.. It used the information collected through its monitoring work to challenge the Reagan Administration’s policy of supporting right-wing governments and rebel groups in Central and South America. Americas Watch’s report itself had little impact on the human rights situation of the countries it covered, but the organization’s ruthless humiliation towards the Reagan administration forced Reagan to reconsider the role and legitimacy of Helsinki Watch.

Another consequence of the establishment of Americas Watch was that Helsinki Watch embarked on the road of unlimited expansion. By separating human rights from the Helsinki Accords, the organizations hook off the shackles that previously limited their scope. Instead of adjusting its legitimacy model to justify its interest in a particular individual’s destiny, the organization began to focus on fields that were in line with its stated principles. To prove its impartiality, the organization expanded its geographical coverage and legal basis to include abuses by the left and right, the government, and rebel forces. Since there was no natural boundary to limit this pursuit of balance, the scope of the organization was increasingly expanding.

3 The End and a New Start: Human Rights Watch in the Post Cold War Era

By the late 1980s, Human Rights Watch had become an international organization dedicated to defending human rights around the world, but the responsibilities of its various committees were not uniform. The regional committee in Europe was still bizarre. Helsinki Watch retained many commitments that other committees did not have. It still operated in accordance with the Helsinki Accords, and mainly monitored the Soviet Union and Communist countries in Eastern Europe.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War, the original motivation for the establishment of Helsinki Watch disappeared. However, the work of Helsinki Watch had not yet been completed. Facts have proved that newborn democratic countries are fragile and need help and guidance from experienced democracy practitioners. Therefore, the collapse of the Soviet Union did not mean that Helsinki Watch had lost its value of existence. Instead, it proved that Helsinki Watch’s previous work in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union had value: it helped the world fight against this evil political system. After the Cold War, Helsinki Watch’s new goal is to help new independent countries that needed help. Human Rights Watch World Report 1989 pledged that “as before, Helsinki Watch will be there—to observe, to report and to help. The struggle for human rights in Eastern Europe is far from over. To the contrary, it is just beginning”.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the self-awareness of Human Rights Watch was still influenced by the logic of Helsinki Watch to some extent. However, as time went on, the importance of the model formed in ideological confrontation declined, and the organization accepted more general tasks. Just as Human Rights Watch was trying to expand its scope, Robert Bernstein, in an op-ed article in the New York Times, publicly denounced the organization he founded for deviating from its “original mission” and ignoring differences between open and closed societies: “Human Rights Watch had as its original mission to pry open closed societies, advocate basic freedoms and support dissenters. But recently it has been issuing reports on the Israeli-Arab conflict that are helping those who wish to turn Israel into a pariah state”.

Bernstein’s distinction between “open” and “closed” societies reflected a fundamentalist sense of responsibility, even though Human Rights Watch at that time already deviated from its original mission. The organization embarked on a road of expanding the scope of its monitoring work from the moment when it decided to respond to Reagan’s new understanding of the Cold War by seeking to prove the universality of its own principles. Bernstein’s concern made sense, but in fact, the only goal of Human Rights Watch’s current work is to expand fields where its voice can be heard while maintaining its legitimacy. The expansion of those fields has nothing to do with whether a society is open or closed, nor a political party is left-wing or right-wing. Even the relationship with justice has gradually become estranged. Humanitarian disasters that can trigger compassion are the only thing that Human Rights Watch has interests in.

4 The Way to Write a Story: AMuch Questioned Method of Investigation

As the scope of HRW’s focus expanded, its investigation work began to multiply, but many of the organization’s traditions were preserved in the new working environment.

The first is the symbiotic relationship with the U.S. government. Although Human Rights Watch is no longer directly involved in the implementation of the U.S. government’s foreign policy and provides feedback, it is still trying to maintain contact with the government. One of the important ways is to hire former government employees. Although these people are in the minority of HRW’s employees, hiring them can help keep the organization understands the government’s working mode. At the same time, the networking of these employees is invaluable for an international NGO.

Another issue concerning Human Rights Watch that has often been criticized is its opaque source and use of its funds. On June 29, 2016, the U.S. non-profit organization Transparify released its 2016 financial transparency report on 200 think tanks and lobbies worldwide. Among the 43 U.S. think tanks and lobbies in the report, Human Rights Watch and United States Institute of Peace were “two-star”, and Open Society Foundations came last for the third consecutive year (no star). In response, Human Rights Watch spokeswoman Emma Daly said that more detailed information was published in its paper annual report, “we didn’t make it public online because many of our donors, especially elderly donors, don’t want us to”.

Hiring former government employees and refusing to make its financial condition public will not really undermine the credibility of an organization. As long as the organization can do its job well, all these accusations will not be frightening, but the problem is that Human Rights Watch has been unable to put its ideas into practice. Growing evidence suggested that HRW’s act of maintaining its legitimacy through false information did not end with Reagan’s stepping down. On the contrary, the organization went even further to produce human rights reports in favor of its paymasters in exchange for financial support. In 2020, the HRW Board of Directors, under external pressure, admitted that HRW accepted a $470,000 donation from Saudi real estate magnate Mohamed Bin Issa Al Jaber under the condition that HRW should downplay Al Jaber’s abuse of labor and not support LGBT advocacy in the Middle East and North Africa.

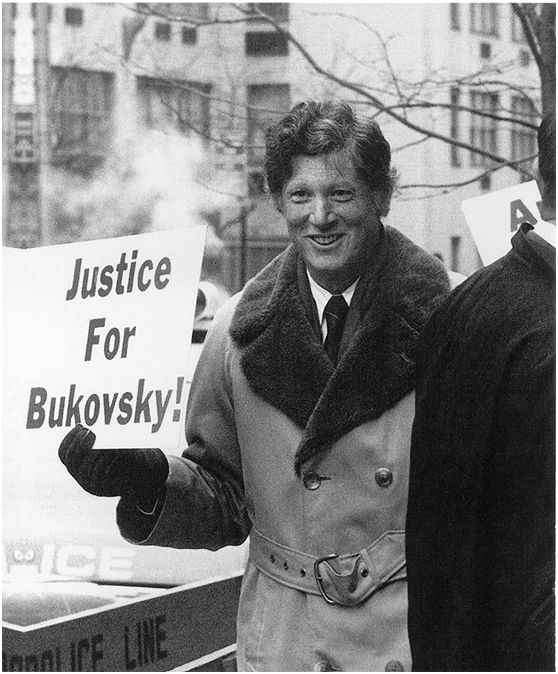

The strong bias in HRW’s reports has also aroused dissatisfaction from many human rights workers. On June 26, 2014, dozens of human rights activists staged a small protest in New York, marching from the office of the New York Times to the Empire State Building where Human Rights Watch is headquartered. They criticized the New York Times and Human Rights Watch for serving as tools of the U.S. government and the Central Intelligence Agency, especially for their attacking and smearing the Venezuelan government in recent years and refusing to condemn the U.S. government’s involvement in major human rights violations such as the 2004 Haiti coup d’étatand the 2009 Honduras coupd’état. The protestors said that Human Rights Watch’s condemnation of the Venezuelan government was mainly based on unconfirmed statements from the Venezuelan opposition and particular examples taken out of context, ignoring or legitimizing the planned violence of the Venezuelan opposition.

Israel also dismisses HRW’s legitimacy, arguing that its publications reflect a lack of professional standards, research methods, military and legal expertise, and deep-rooted ideological bias against Israel. Israel believes that Human Rights Watch pays disproportionate attention to the condemnation against Israel, and its publications related to Israel are not trustworthy. Israel accused HRW of producing its report on the Israel-Palestine issue entirely from the Palestinian perspective without considering Israel’s position and spreading fake, distorted, and unsubstantiated accusations against Israel. Human Rights Watch played an important role in producing the Goldstone Reportwhose credibility was eventually lost. The organization also submitted numerous statements to UNHRC, equating Israel with Hamas and wrongly accusing Israel of “deliberately” killing civilians.

China, as the inheritor of the Soviet Union in ideology and the biggest cooperative partner and competitor of the United States in economy and technology, has long been the focus ofHuman Rights Watch. To prove that China’s current ruling model and political system are extremely wrong, Human Rights Watch has written reports on all issues that can make mischief, including Xinjiang, Tibet, Hong Kong, and the rights and interests of ethnic minorities. However, after the Chinese government made all these places fully open to visitors, HRW’s observers did not go there to investigate but limited their scope to merely talking with the “victims” of relevant events. In the end, Human Rights Watch accused China of human rights violations in many regions and fields based on imagination and guessing rather than evidence.

Not only governments have questioned Human Rights Watch, but many scholars have also criticized the composition, methods, interpretation techniques, and inaccuracy of HRW’s reports. The Transformation of Human Rights Fact-Finding Co-authored by Philip Alston and Sarah Knuckey represents the most systematic criticism against the organization in academic circles. The book points out that the international community is paying increasing attention to NGOs’ investigation reports, believing that these reports can fairly and accurately capture the blind spots of governmental bodies. But the reality is that many organizations, including Human Rights Watch, have failed to perform their social functions. The problems in the world are ever-changing and each one exists and develops in a different context. However, Human rights Watch failed to see problems from a more flexible perspective according to changes in the environment and the times. At the same time, the composition and methods of its report are far behind the times, making the organization’s work’s been questioned much more frequently.

5 A Ghost in the Old Era

Since 1978, Human Rights Watch and its predecessor have witnessed many changes in American ideas. Roosevelt’s inspiring and enthusiastic words in 1944 are still ringing in our ears, but the United States is no longer in its prime. What really made Human Rights Watch fail is not the ever-changing governing philosophy of successive US presidents, but the defects that have always existed in the values and political system of the United States.

The organization first wished to appear as the spokesman of the democratic bloc, but the change of regime made it realize that no bloc was permanently safe and constantly proving its legitimacy in a new environment was the key to its survival. Different from the United States which lacks reform, Human Rights Watch is obsessed with reforming to survive, and eventually became a ghost in the Cretan labyrinth after many policy changes. It no longer tries to improve human rights, and it blocks anyone trying to solve the problem. Human Rights Watch, the ghost in the labyrinth, has come to the end of its historical mission.

(Disclaimer- Brand desk content)